Although Pritzker winners have included several members of the architectural avant-garde, Mayne has been considered one of the most polarizing figures in architecture. His verbal battles with clients and builders are legendary in the profession. And there is nothing traditionally beautiful or explicitly welcoming about his designs.

"I'm interested in conflict and confrontation," Mayne said.

His buildings, often cloaked in canted or folded metal screens, giving them a dramatic silver-gray cast, have a muscular presence. They use fragmented forms to express the anomie of contemporary life — and of sprawling, centerless Los Angeles in particular.

"There is a real authenticity to the work that we liked," said Gehry, a member of this year's Pritzker jury. "There's no denying he has carved out his own path and hasn't strayed from it. He's not copying anybody else."

So instead of trying to do something about "the anomie of contemporary life" he's going to celebrate it, and make it that much worse. And yes, that's Frank Gehry, Lord of All that is Shapeless and Ugly, on the jury that gets to decide who will be honored for most monumental lack of taste each year. How wonderful for him.

The Pritzker family, after which the prize is named, is one of Chicago's most influential families, and almost certainly its wealthiest. They helped build this town, and now I guess they want to help build it again, only uglier this time.

Speaking of building Chicago, the crappy two-story commercial building, topped by a three-story billboard, that occupies the prime real estate between Marshall Field's and the Chicago Theater is coming down soon. While this alone should probably be cause for joy, it's being replaced by one of those characterless modern glass towers I hate so much. This is really a shame, considering how the rest of the neighborhood has been looking up recently. Old buildings are being rehabbed back into shape, and the areas new construction has been attractive and even exciting. The new condo tower going up between Marshall Field's and the Cultural Center, for example, is perhaps my favorite buildings in Chicago - the controversy of having the Mayor move to an address north of Madison for the first time since Cermak took power in 1931 aside (actually, didn't Jane Byrne briefly live at Cabrini?). Wow, that was quite a sentence.

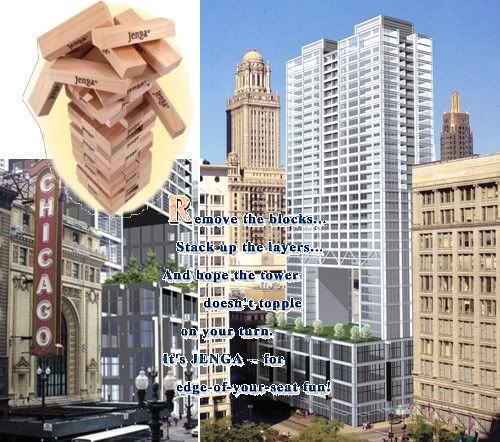

Anyway, the new building at State and Randolph is terrible. There's no way to do a glass box and not have it be terrible, actually. The architect here tries, however, by leaving a big gap in the building to "break up" the monotony. Or something. The effect is actually to make the thing look like a half-played game of Giant Glass Jenga. Oh well, at least the billboard will be gone.

Speaking of Modernism run amok, let's return for a moment to the new Pacific Garden Mission design by Stanley Tigerman. People are still gushing about it. Tigerman is known for being particularly interested in applying architectural desing to solving social problems (a refreshing change from Mayne, who just wants to celebrate our dysfunction). "It is not just housing for homeless people, it is housing designed to reintegrate them back into society, with green elements that will be uplifting for people on the bottom rungs of society," said Phillip Snelling, one of the Mission's attorneys, said in an interview last week. Oh, so that was the problem. Green space! Homeless people just don't get enough of the outdoors, I guess. You'd think they'd be sick of green space after a few weeks of sleeping in the park.

Don't get me wrong, I'm in support of building a new homeless shelter in the South Loop. I think it's needed. But it's always interesting to me how middle class reformers and idealists, from Jane Addams to the present, try to help the poor and desperate by either trying to make them more like us, or by giving them things the middle class wants. Jane Addams, for example, tried to introduce poor West Side immigrants to Shakespeare and opera and painting. Welfare reform tries to help poor families by getting single mothers of young children to participate in the craptastic service sector economy of Wal-Mart and Subway. Again, not that I have any opposition to Shakespeare or gainful employment, both of which I personally benefit from. But any time the haves give something to the have nots, I'm suspicious - the relationship is inherently a paternalistic one. This is often unavoidable but definitely uncomfortable for all parties. In social work, of course, you address this head on by working with clients to arrive at collaborative goals. But in designing programs or making large-scale investments, you're inevitably giving people something without giving them much choice about what that is.

Architecture ends up reflecting the values and priorities of the time in which it was built. Back in the age when the desperate poor were thought to need art and literature, buildings were flowery and tried to be beautiful. Even Sullivan, thought of as the pioneer of the modern office tower, included elaborate decorative detail. True, it wasn't reflected in the broad design of the building, but that was because it was on a human scale, not a grand scale. He preferred to decorate stairwells and light fixtures rather than giant stone columns. It was an architecture for democracy, not empire. Today's buildings continue to reflect the mantra of "simple, clean lines" and "open spaces." Perhaps our lives are so full of useless clutter we have come to value emptiness, simplicity, space.

I doubt most homeless people share that problem.

No comments:

Post a Comment