American Girl, as some of you know, is some kind of cult in which girls dress like their dolls and take them out to eat at a special restaurant/doll store on the Magnificient Mile. That's kinda weird, but that's not the controversial part. The controversy is that each doll comes with a story about where she came from , where she lived, etc. The stories can be set in any period of history, but some of them are modern day. The newest doll is Marisol Luna. The story that comes with the doll states that she's from the Pilsen neighborhood on the near southwest side of Chicago, but recently moved with her family to Des Plaines, a suburb close to O'Hare airport.

The old neighborhood "was no place for me to grow up," the doll's story says.

"It was dangerous, and there was no place for me to play."

The good people of Pilsen were pissed off.

"It's very offensive and it's really a slap in the face to the hardworking people of the Pilsen community," said Alvaro R. Obregon, who lives near where the doll, Marisol, supposedly lived before setting out for suburban Des Plaines.

The resulting firestorm is the biggest ruckus raised over a toy since they recalled the Battlestar Galactica fighter planes back when I was 7 years old after some idiot kid choked to death on the little plastic "laser bolt," and reveals a lot about what's really going on in America.

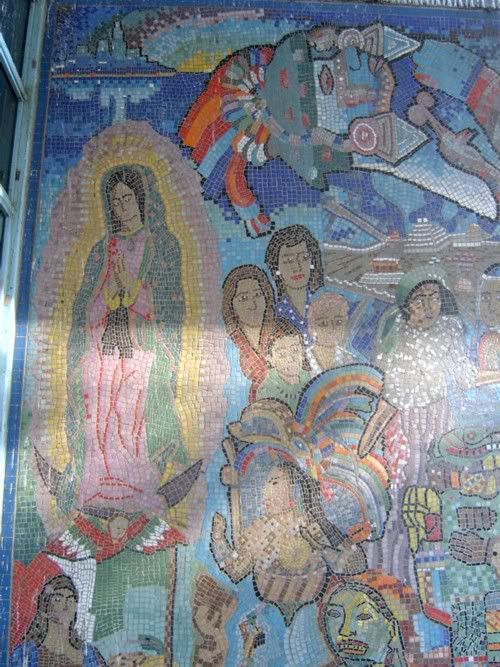

Pilsen is actually a wonderful place. Every time I go there for work I'm thrilled to be there. Originally build by Bohemian immigrants and named for the Czech city of Pilzn, the neighborhood is just south and west of Chicago's Loop, sandwiched between Chinatown and the University of Illinois - Chicago. For at least the past half century it's been the first stop for Mexican immigrants arriving in the Chicago area. Typically it's been a transitory sort of place - once established, immigrants have tended to move southwest along the canal, settling in Little Village and, in recent years, the old Mafia suburb of Cicero and beyond. There's a thriving arts community at the neighborhood's eastern edge, not to mention the Mexican American Fine Arts Center Museum, but it's mostly known for the colorful murals which are nearly ubiquitous. Cafe Jumping Bean is in Pilsen, as is the classy Nuevo Leon. And there's an awesome diner at 18th and Damen that gives you free soup with your lunch, no small thing in a Chicago winter.

Mostly the neighborhood is a working class, family type place with lots of kids and churches. Professionally I know a lot of good people there, working to make the neighborhood a better place to live and grow up in.

But also, indisputably, it's gangland. I'd love to be able to write a post and say the media has given a perfectly good neighborhood a bad rap and scared away people and investment, etc, with outlandish distorted stories about crime, and I could. But that would only be half of the truth. Like most of Chicago, things are much better than they were in the bad old days, but that's not really saying all that much. While urban minority neighborhoods have never been the cesspools of vice, anarchy and violence that terrified suburbanites imagine them to be, the reality can still be pretty depressing. Many of the neighborhoods young people join gangs, and some of them don't make it to adulthood as a result. While these fatalities may be down to a handful a year in the neighborhood, it's still the kind of risk parents don't want to expose their children to. So why would neighborhood people be so angry about the story of a family moving out to the suburbs?

"Pilsen is more than just a place on the map, or a typical Latin community that has drive-bys and is unsafe and dangerous," Alejandra Ibanez, executive director of the Pilsen Alliance, told Chicago Public Radio. "That's just a typical outside view of Latino neighborhoods. Pilsen is a neighborhood. Families live here. They raise children here. Raise grandchildren here. They've made it into the vibrant community it is, with a grand history and amazing cultural institutions. So it's offensive to us who live here and have made our lives here."

There's more to it than that. Many people blame the flight of the aspiring middle class from neighborhoods like Pilsen for the hard conditions that exist there. By withdrawing resources that could make the neighborhood better, they create a cycle of decline and disinvestment that turn once thriving neighborhoods into hollowed-out ghettoes. Instead, these resources are invested in the bland, lifeless planned communites of American Sprawl, the mallified opposites of the words "vibrant," "cultural," and often "community" as well. Instead of running from these problems, families could stay and work to fix them. So Pilsen residents are thrilled when lifelong community members attempt to stay in the neighborhood and build decent housing for themselves, right?

Wrong.

Hispanic condo buyers seen as Pilsen threat

Plan for pricier lofts has neighbors wary

By Oscar AvilaTribune staff reporter

Published April 22, 2005

J. Ignacio Gonzalez thinks he can give Pilsen a boost by buying a two-bedroom loft in a condo project planned for an abandoned warehouse. One of his potential new neighbors disagrees and accused the 29-year-old police officer of kicking out his "own people."

"I'm not trying to kick anyone out," said Gonzalez, the son of Mexican immigrants, still fuming about the exchange. "I'm trying to attain part of that American dream, which is to own a piece of property."

The clash over Chantico Lofts echoes many others around the city: Pilsen residents fear the project will displace working-class Mexicans by raising property values, which result in higher property taxes and, ultimately, higher rents.But this battle isn't about outsiders moving in and threatening an immigrant neighborhood's ethnic character. Nearly all those who, like Gonzalez, have put down $1,000 deposits to reserve a loft are Mexican themselves. Many grew up in Pilsen.

Opponents have made Chantico Lofts a rallying point because they fear that the project, believed to be Pilsen's largest condo proposal, will open the floodgates to more high-priced housing.The Chantico Lofts project has become the main target of a campaign called "Pilsen is not for sale." Opponents have scheduled their first major rally against the project next week.

Even attempts by the developer to embrace the neighborhood's Mexican character--the project's namesake is the Aztec goddess of the home, and a plaza will incorporate an existing mural of the Virgin of Guadalupe--have been derided by some as exploiting Mexican imagery for profit.

Huh? So residents don't want people to move out, but they don't want them to move in, either. A majority of Americans view their home as an investment, and want that value to grow. But in rental neighborhoods like Pilsen (and Bucktown), rising property values are a Bad Thing. As assessments grow, taxes increase, and are passed on to residents in the form of higher rents and less maintenance. In addition, Pilsen residents have seen their former neighbors north of the viaduct in the old Maxwell Street Market area evicted en masse as the entire neighborhood was razed to make room for kitchy new condos and student housing. They fear they will be next. Will they?

Quite possibly. The real ticking time bomb for the neighborhood is its degenerating stock of late nineteenth century wood frame houses. These buildings, may thrown up in the aftermath of the Great Fire before building code changes banned wood construction in much of central Chicago, have never met code and our now nearing the end of their useful life. Many of these are scarcely habitable and desperately need to be replaced, but under current economic policies it's impossible to build affordable housing without government subsidy. Construction simply costs too much for houses to be sold for less than $100,000 even downstate, let alone right down the street from Chicago's central business district.

The Chantico Lofts project has caused a split among advocates of affordable housing. Some say Pilsen residents should fight developers tooth-and-nail while others want to become partners to create mixed-income projects. Chantico's units will range from $150,000 to $375,000, dirt cheap for new construction in Chicago. As part of a compromise, the developer has pledged to set aside 21 percent of the units for residents making below the city's median income. That's about as good as it gets under current conditions.

If places like Pilsen are to survive, there needs to be a coherent government policy on creating affordable housing - tax credits, inclusive zoning, etc. But even that may not be enough. To halt the destruction of neighborhoods, local and state governments need to raise money from income taxes, not property taxes. Income taxes take money from people based on their ability to pay, not on what someone might offer for their house were it for sale.

Such a change will probably come too late for Pilsen residents. Their neighborhood is a little too cool, a little too accessible, a little too close to the Loop. Ironically, gang violence may be the only thing that has kept the neighborhood cheap enough for residents to afford to stay there. As the murder rate falls and schools improve, rising rents and new developments become inevitable.